The Automation Trap

Robots, Old People, And What Happens When Nobody’s Left to Buy.

Grüezi!

1. The Productivity Paradox

In 2024, China installed 295,000 industrial robots – more than Japan, the United States, South Korea and every other market combined. Chinese manufacturers captured 57% of their domestic market. Operational robot stock hit 2 million units.

The Western policy response? Frame it as a competitive threat. Chinese firms get subsidies, they automate, costs fall, Western producers lose market share. The solution? Tariffs.

But if automation creates unfair advantages, then every country that successfully puts robots on production lines – Germany, Japan, South Korea – becomes a tariff target.

What tariff advocates won’t acknowledge is that they’re not responding to Chinese automation at all.

They’re responding to a domestic distributional failure whilst pretending it’s a trade problem.

Automation pushes out workers whilst concentrating returns to capital. That requires domestic institutional responses: tax systems that capture productivity gains, wage structures that share them, retraining programmes that redeploy displaced labour.

Tariffs solve none of this.

That’s because they merely shield domestic firms from foreign competition without addressing how those firms distribute their own automation gains.

Worse, they actively discourage domestic automation by reducing competitive pressure – the opposite of building productive capacity.

The real question isn’t how to fight Chinese robots. It’s how to ensure automation’s benefits spread rather than concentrate – a challenge that every industrial economy faces regardless of trade.

The problem is – most countries lack the institutional capacity to do this.

China’s answer is state-controlled finance channelling capital through policy banks.

The Nordics’ answer is through progressive taxation recycling productivity gains into universal services.

America’s answer is house prices and stock portfolios – letting capital markets do the work fiscal policy can’t.

Whether any of these models can sustain depends on foundations most countries lack.

And even where those foundations exist, they’re colliding with something more fundamental than policy failure: the demographics that made any of these models possible are inverting across all major economies simultaneously.

2. Three Models, One Vanishing Foundation

Nordic but nice – Redistribution: the unscaleable model

Sweden, Denmark and Norway prove high automation and low inequality can coexist through progressive taxation, universal social insurance, and labour representation. Tax-to-GDP ratios above 40% fund redistribution that recycles productivity gains back into broad-based consumption.

So why doesn’t every country just copy the model?

State capacity. The Nordic model requires administrative machinery, tax collection capability, and political consensus that took decades to build and that most democracies simply don’t have.

Nordic redistribution requires tax-to-GDP ratios above 40%. Denmark hits 46%, Sweden 43%. By contrast, the United States collects 27% of GDP in taxes. Decades of anti-tax lobbying have made increases politically toxic.

France collects 46% but runs persistent deficits, with any reform attempts triggering mass protests – high taxes without the institutional coherence to manage them or the economy to sustain them.

The Nordics built extensive welfare states over the postwar decades and locked in political support across multiple election cycles and coalition governments. Countries without that foundation can’t simply import the technical mechanisms.

You need administrative capacity to collect taxes efficiently. You need political coalitions spanning regions and economic sectors. You need wage-setting institutions that command legitimacy.

Most democracies lack all of the above.

Anglo-American attitudes: a model running out of people

By contrast, the US and UK manage automation through inequality.

Productivity gains flow to capital owners whilst manufacturing hollows out.

Consumption survives through consumer credit and rising house prices and stock portfolios – for those lucky enough to own shares or homes.

The mechanism worked for forty years. Rising property values and equity portfolios from the 1980s created wealth effects that sustained spending without wage growth.

US household consumption rose from 62% of GDP in 1980 to 68% by 2023. The Boomers – 76 million people born between 1946–64 – became history’s wealthiest demographic cohort and a consumption machine.

But roughly 70% of US wealth is in the hands of over-55s. This consumption model lasts only as long as Boomers spend down their retirement savings, sell their homes, and cash out their portfolios.

By the late 2030s, that wealth will have depleted. Younger generations can’t replace it – they have lower home ownership, higher debt, weaker wages. Automation continues suppressing their earnings whilst inflating assets they don’t own.

China’s robot trap: automation as survival, not choice

China faces a variation on that theme. It is building new workers. Robot density nearly doubled from 246 per 10,000 workers in 2020 to 470 in 2023.

To power that – and AI – the country is building energy capacity frantically. Some 429 gigawatts of generation were added in 2024 alone, including 277GW of solar and 80GW of wind – even though grid bottlenecks already waste 15–20% of renewable energy in some provinces. Those are fixable infrastructure problems.

The unfixable problem is people. China’s working-age population peaked in 2015 and will drop by over 100 million by 2040. For China to maintain its current GDP will require productivity gains of roughly 11–12% annually – just to offset workforce decline.

China will need 1,000–1,200 robots per 10,000 workers by 2040, on a par with South Korea’s current world-leading level. That means going from 2 million operational robots to 9–11 million. At current installation rates, China will reach only 7 million.

But this isn’t just about labour supply. It’s about what happens to consumption when your workforce collapses.

Private consumption was 39.6% of GDP in 2023 versus 68% in the US. China’s consumption suppression is now demographically locked in regardless of policy. A shrinking, ageing workforce means fewer wage earners, collapsing household formation, and far more retirees depending on each working adult. Property prices begin to crumble with fewer households forming. Government revenues fall as tax bases drop whilst healthcare spending surges.

Even if you can automate fast enough, there’s a harder problem: you can’t automate your way out of having nobody to buy what the robots produce.

This is where the logic of tariffs as a redistribution-substitute breaks down completely. China is automating because its workforce is disappearing – not to undercut Western wages. The productivity gains aren’t optional – they’re demographic survival. But those gains concentrate in capital whilst the consumer base erodes.

The pattern beneath the failures

So if the Nordic model can’t scale beyond small, homogeneous countries, and the Anglo-American model is running out of wealthy old people, and China faces demographic consumption collapse despite furious automation, the challenge shifts from domestic redistribution to international capital allocation. Where does future demand come from when every major economy is ageing simultaneously?

Finding consumers requires looking beyond industrial economies entirely – to the only places where working-age populations are still expanding.

3. Where the Consumers Are (But Not the Money)

Africa will add 950 million people by 2050 to reach 2.5 billion. By mid-century, one in three young people globally will be African. The continent’s working-age population will increase from 883 million to 1.6 billion. South Asia will remain demographically “young” through mid-century.

These regions represent the only expanding consumer bases globally. China ages rapidly. Europe’s population shrinks. The US will grow only through immigration – which is now politically constrained.

The demographic heartlands of future demand are clear. The problem is purchasing power.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s average income of $1,440 per capita means hundreds of millions of future consumers who can’t afford to buy anything yet. Demand is moving to the economies least equipped for capital accumulation.

This creates a chasm that tariffs and domestic redistribution can’t bridge. The problem now requires redistribution across borders, not within them.

The closing automation window

Humanoid robot costs fell 40% between 2022 and 2024. China’s basic Unitree G1 retails at $16,000. Unit price isn’t the full cost – integration, maintenance, downtime and supervision multiply the burden. But the direction of travel is clear.

Optimistic scenarios place full automation viability in developing economies around 2030–35 – the point where annual robot costs fall below $10–15,000 and automation begins to outcompete even low-wage economies like Vietnam or Bangladesh. Conservative estimates push the timeline back a decade.

The uncertainty matters less than the fact that robot economics are constantly improving whilst labour costs in successful manufacturing hubs are only rising.

Countries that build manufacturing capacity in the next 10–15 years can potentially reach middle-income status before automation closes the labour-cost advantage. Those that don’t will face cut-throat competition from automated production near consumption markets.

The historical development pathway – export-led industrialisation bootstrapping domestic consumption – is closing just as a billion young Africans reach working age.

Where capital meets need

If any institution could bridge this timing gap, it should be the one with the most capital, the strongest industrial overcapacity, and the clearest strategic incentive to create future demand.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative represents exactly this opportunity: using Chinese surpluses to build infrastructure that could raise productivity across the Global South, creating the future consumers China, and the world, needs.

The fit looks perfect on paper. China has fast-automating overcapacity and declining domestic demand. BRI partner countries have young populations but lack capital.

Building their productive capacity should create consumption bases that can absorb Chinese production through the 2030s and beyond.

So why isn’t it working?

4. China’s Trillion-Dollar Experiment

Since 2013, China has committed over $1 trillion across 150+ countries – perhaps $80–90 billion annually at its peak, although now down to $50–60 billion.

If this were working at a system level, we’d see rising African incomes translating into sustainable demand for Chinese production.

We’d see manufacturing capacity and domestic consumption growing fast enough to absorb Chinese overcapacity through the 2030s and beyond.

It isn’t happening at that scale.

The wrong kind of capital

BRI concentrates on infrastructure to ease trade rather than building consumption capacity. Most of the money that goes to Africa is spent on ports, railways, and power generation that help distribute China’s exports and ship out African resources. Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway cost $5 billion to build, operates at a loss, and primarily trundles Kenyan commodities to ports and Chinese finished goods inland.

Only about 15–20% of BRI cash goes to manufacturing investment: Ethiopian industrial parks employing tens of thousands in garment manufacturing, Special Economic Zones in Egypt and Uganda transferring production capacity, and agricultural processing facilities adding value to coffee, cocoa, and tea exports.

To make a difference this ratio would need to flip.

But it won’t, because this investment pattern isn’t an accident. It reflects what Chinese domestic politics can support: infrastructure projects that employ Chinese construction firms, consume Chinese steel and cement, and secure much-needed commodity supplies.

Genuine development investment – grants for education, technology transfer for local manufacturing, support for institutions to enable broad-based prosperity – would require permanent capital outflows without tangible returns to Chinese producers.

China’s citizens can’t get behind that whilst facing demographic and fiscal troubles at home, and when China too still has swathes of territory inland crying out for development cash.

Chinese investment has evolved – from 30% to 70% private sector involvement, from pure infrastructure lending to equity stakes in manufacturing, from coal-fired power to renewable energy.

The shift towards private sector involvement and equity investment does represent adaptation.

But the fundamental tension remains: African development needs consumption-building investment; Chinese political economy needs outlets for producer goods overcapacity.

The scale and timing mismatch

Africa needs roughly $100–130 billion annually in infrastructure spending through 2040. Even at its peak, BRI covered only 60–70% – and most of that spending flowed to Eurasia, not Africa. The current $50–60 billion spread across 150 countries is insufficient.

The maths of lending to low-income countries becomes treacherous. When you lend to countries with very low per capita incomes to build infrastructure, those projects generate returns in local currency whilst the loans are denominated in dollars or yuan. Unless the infrastructure triggers rapid GDP growth, debt quickly becomes unsustainable.

Most projects don’t. Zambia restructured $6 billion in debt after the copper price collapsed.

Infrastructure gets built, debt accumulates, incomes don’t improve – and the debt burden itself constrains future investment in education and healthcare that might build consumption capacity.

But the timeline problem is more fundamental. China’s consumption crisis intensifies through the 2030s as its working-age population falls. Even if BRI investments were perfectly targeted, infrastructure spending takes 10–15 years to generate returns. You can’t solve a 2030s consumption problem with investments yielding results in the 2040s.

The currency problem

The currency mismatch cuts deeper still. Chinese overcapacity is denominated in real goods – solar panels, steel, electronics. The problem isn’t just state-level trade – African economies must produce something Chinese consumers need to earn the currency to service debt and buy Chinese goods. But what does Kenya or Tanzania produce that Chinese consumers need at scale?

Commodities, perhaps – copper, cobalt, oil. But China already sources those, and commodity exports don’t generate the broad-based wage employment that creates mass consumption. Manufacturing for African domestic markets could generate employment and purchasing power – but that requires Chinese firms to see African consumers as the market, not Chinese consumers. Some movement does exist. Chinese household appliance manufacturers, building materials producers, textile firms are serving African markets. But volumes remain small.

What it actually delivers

Belt and Road delivers geopolitical leverage, diplomatic alignment, commodity supply chains, and political influence. These matter for China’s strategic positioning. They don’t solve the domestic consumption crisis.

BRI keeps Chinese construction firms and steel mills running through China’s economic transition. This is demand management for Chinese producers, not demand creation in partner countries.

And even if China flooded Africa with perfectly structured infrastructure investment, that doesn’t automatically generate institutional foundations for broad-based prosperity. Governance capacity, rule of law, education systems, financial depth, political stability all take generations to build.

Vendor financing can work when the customer will be able to afford the products within the debt payback period. That requires infrastructure, manufacturing investment, and institutional development all converging to create purchasing power before demographic windows close and automation costs fall below African wage rates.

So if China with $1 trillion and clear strategic need can’t bridge the gap, could anything else?

Does history have any lessons for us?

5. Why History Won’t Be Repeating

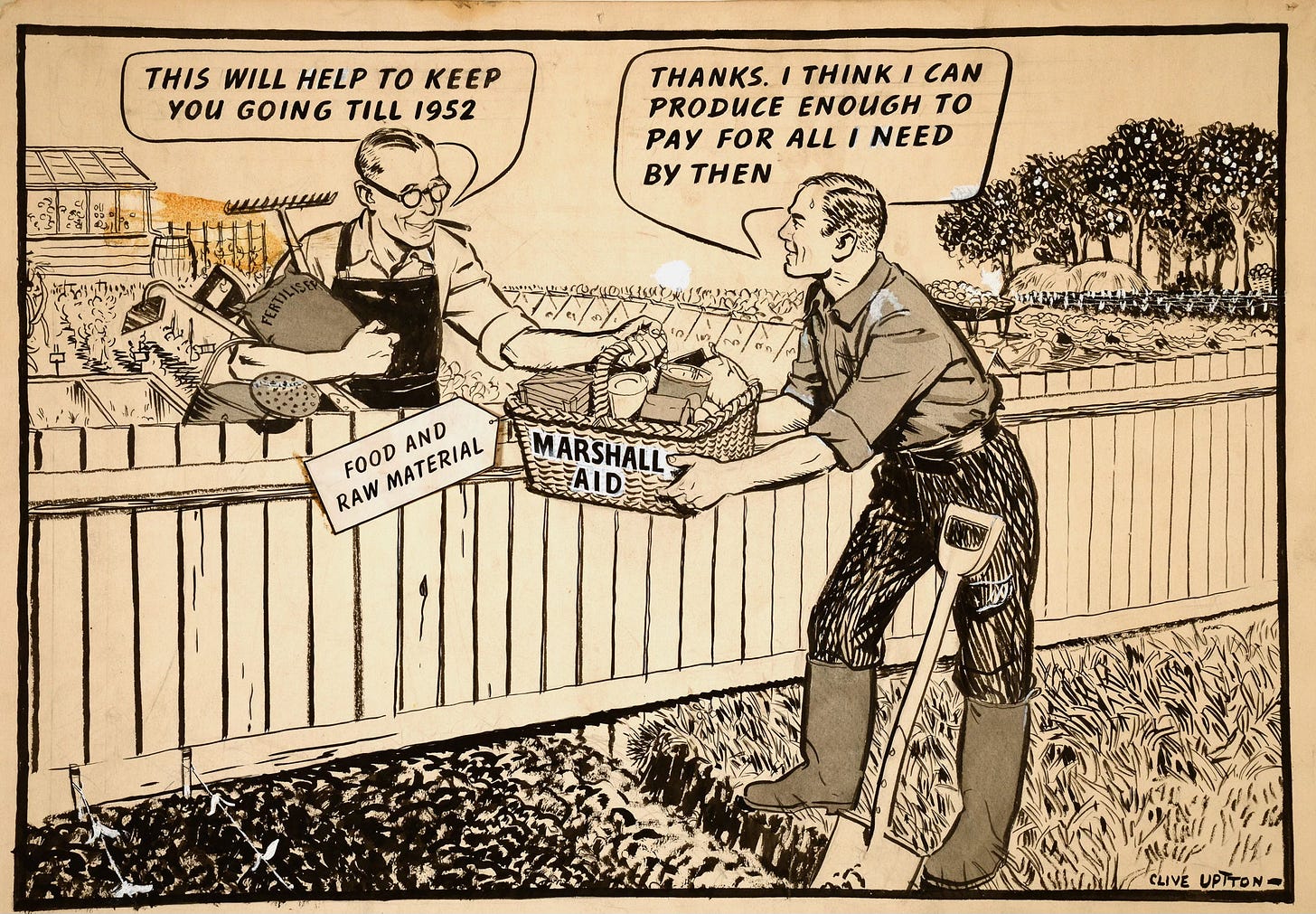

The example most frequently cited by optimists is the Marshall Plan. After 1945, America rebuilt European and Japanese productive capacity through capital transfers and open markets. Within two decades consumption recovered and global growth resumed.

Could some coalition fund infrastructure, transfer technology, and enable industrialisation across the Global South? Could African and South Asian demographics provide the global consumption base that ageing societies can no longer supply?

This is to misunderstand what made postwar reconstruction work – and the answer reveals why the current crisis can’t be solved the same way.

What made it possible

Between 1948 and 1952, America transferred $13.3 billion to Europe – roughly 1.1% of GDP over five years. In today’s dollars that’s perhaps $150 billion annually. Substantial, but not the primary engine of recovery.

What created demand wasn’t capital. It was people born in the right places at the right time.

European births jumped from 7.8 million in 1945 to 10.8 million by 1964. That baby boom – replicated across Western Europe and North America – generated the consumption base that absorbed postwar productivity gains for three decades.

The Marshall Plan injected capital into mature societies with young, rapidly expanding populations whose consumption needs would grow for decades. That’s what made it work.

Here’s what postwar institutions actually were: Bretton Woods, GATT, dollar hegemony looked like pillars of a universal order but were really just instruments of demographic arbitrage.

Young European and Japanese populations produced. Young American populations consumed.

Capital and goods flowed in both directions. Everyone got richer together because everyone’s working-age population expanded simultaneously.

Political consensus held because the threat of Soviet communism dangled like a sword of Damocles over everyone.

Everyone called this “the international order.” It was actually a contingent settlement that only worked whilst specific demographic conditions held.

What’s different now

A Marshall Plan for Africa or South Asia would inject capital into young populations – but these regions lack the institutional foundations that made European reconstruction possible.

Postwar Europe had literate populations, legal systems, property rights, recent experience with industrial capitalism. Cities were levelled but institutional memories remained.

Sub-Saharan Africa has very low incomes, 40% of the population is under 15, governance capacity is marginal. You can build infrastructure – BRI proves that – but it doesn’t automatically generate the tax capacity, rule of law, and financial depth required to convert capital into sustained consumption growth.

More fundamentally, the timeline is wrong. China’s consumption crisis intensifies through the 2030s. Western consumption contracts simultaneously. African working-age population won’t peak until the 2050s–60s.

Even with capital transfer at Marshall Plan scale – politically impossible given fiscal constraints across all advanced economies – the mismatch spans two decades. Productivity gains from automation happen in the 2030s. The demographic expansion required to absorb them doesn’t happen until the 2050s.

US hegemony in hindsight

American hegemony wasn’t primarily military dominance or monetary privilege. It was a consumption subsidy mechanism.

The United States ran persistent trade deficits to absorb global production. Dollar hegemony enabled this by making American debt costless – other countries accumulated Treasury bonds whilst Americans consumed their exports.

Boomers’ houses appreciated from $30,000 in 1970 to $400,000 by 2020. Their retirement accounts swelled with decades of equity gains. They could borrow against rising home values and spend the proceeds.

This looked like “normal” economics because it operated continuously since 1945. Everyone assumed it reflected a rational equilibrium rather than a historically specific demographic numbers game that only worked whilst the hegemon had an expanding, wealthy consumer base.

That “natural” state of affairs is ending. By 2040, America won’t have the demographic capacity to play consumer of last resort. The Boomers will have spent down their retirement savings and sold their houses to fund twilight care and artisanal coffins.

Younger Americans can’t sustain 68% consumption-to-GDP with lower incomes, higher student debt, and no property equity to borrow against.

China can’t replace American demand – its demographic trajectory is worse. Europe has shrunk into irrelevance as a consumption base.

The international order wasn’t a stable equilibrium. It was a one-time transfer mechanism that worked for 75 years because of demographic conditions that will not recur.

The implications

Understanding the postwar order as temporary demographic arbitrage rather than permanent institutional architecture clarifies why current policy responses keep failing. Tariffs, currency manipulation, industrial policy – all assume the problem is competitive positioning within a stable framework. But the framework itself is dissolving because its demographic foundation has inverted.

This reframes everything examined earlier. The Nordic model works only in small countries because it requires tax capacity built during demographic expansion – conditions that no longer exist. The Anglo-American wealth model depended on asset appreciation driven by expanding cohorts of buyers – now reversing. China’s automation isn’t unfair competition – it’s desperate mathematics to offset workforce collapse.

Which means the 2030s become the collision point where every contradiction hits simultaneously.

6. The Cascading Collapse

These aren’t separate national challenges that might offset each other through trade adjustment or currency movements. They’re reinforcing failures in a system that only worked when all major economies had expanding workforces and at least one had both expansion and wealth.

When those conditions disappear, the failures begin to cascade across borders and accelerate over time.

China 2030–35

Robot density reaches 800–900 per 10,000 workers – short of the 1,000–1,200 target required to offset workforce decline. Private consumption drops below 35% of GDP. Property deflation continues, local government debt restructures trigger banking stress.

The surplus production has nowhere to go. Deflationary pressure becomes permanent. Firms keep producing because fixed costs demand it, but prices fall because nobody’s buying. Profit margins compress. Investment collapses because there’s no return to capital when you can’t sell output.

Therefore BRI becomes unsustainable as partner countries can’t service debt when commodity prices collapse. China faces write-offs or asset seizures, destroying whatever geopolitical goodwill lending generated. The trillion-dollar attempt to create future consumers ends in defaults.

United States 2035–40

The last Boomers exit the labour force, aged 71–89. The property wealth and retirement portfolios that drove consumption for 40 years have been spent down or eroded by market corrections precipitated by demographic-driven selling.

Household consumption drops from 68% of GDP toward 60%. That 8-percentage-point decline represents roughly $2.4 trillion in reduced annual demand – bigger than the entire German economy. Corporate earnings fall. Pension funds face shortfalls. States with older populations see tax bases collapse whilst Medicaid spending surges.

Younger cohorts can’t step up. Automation continues suppressing their earnings whilst productivity gains concentrate amongst capital owners. But capital ownership without consumption demand eats away at capital values. Stock portfolios stop appreciating when nobody can afford to buy what companies produce. House prices stagnate when younger households can’t afford mortgages.

Political breakdown follows economic breakdown. Communities that lost manufacturing in the 1990s now watch service jobs disappear to automation. Immigration restriction and tariff escalation signal policy incoherence masquerading as protection. Neither creates the wage employment or consumption capacity the economy needs.

Africa 2040–50

The working-age population reaches 1.6 billion. Per capita income has risen from $1,600 to perhaps $2,800 – modest growth without the capital accumulation required for sustained consumption expansion.

Automation has closed the industrialisation pathway. Robot costs fell below $15,000 annually, making near-shoring to automated facilities in Mexico or Eastern Europe more economical than labour-intensive manufacturing in Lagos or Nairobi.

The billion young Africans reach working age without the jobs, infrastructure, or capital formation that turned East Asian demographics into economic development.

BRI infrastructure exists but generates no income growth because it was designed for commodity extraction, not domestic manufacturing. Mobile phones are ubiquitous. Buying power isn’t.

Why the breakdown cascades

These aren’t independent crises that might cancel out through offsetting adjustments – they reinforce each other through mechanisms that accelerate once triggered.

Chinese demand contraction eliminates commodity revenue for developing countries, cutting the income they need to service BRI debt. Western consumption decline destroys export markets Asian manufacturing depends on, forcing more production toward a Chinese domestic market that’s contracting.

African demographic expansion without capital accumulation means no consumption base emerges to replace ageing Western and East Asian buyers. BRI defaults cascade into Chinese banking stress, constraining future lending and eliminating even the inadequate capital flows that existed.

Capital flows into asset speculation, cryptocurrency manias, housing bubbles – symptoms of capital with nowhere productive to flow when both production capacity and consumption demand are misaligned geographically and temporally.

Automation continues regardless. Firms automate because competitors do, because labour costs rise, because it’s individually rational. But this creates collective action problems: everyone automates to cut costs, productivity rises, but aggregate demand falls because gains concentrate in capital whilst employment income disappears.

The policy trap

Governments lack the tools to respond.

Monetary policy is exhausted – interest rates are already near zero through the 2020s, and rate cuts don’t create demand when the problem is demographic.

Fiscal policy requires tax capacity and a political consensus that doesn’t exist – and deficit spending doesn’t work when the problem isn’t cyclical demand shortfall but structural demographic shift.

Trade policy has become destructive – tariffs, currency manipulation, export restrictions – because no framework exists for managing permanent imbalances when consumers can’t afford to consume.

The policy response to each crisis makes the others worse. Chinese stimulus flows into investment that creates more overcapacity. Western tariffs reduce competitive pressure for automation, making domestic producers less productive.

Restricting immigration constrains the only source of workforce growth advanced economies have left. Spending cuts to address fiscal imbalances reduce the consumption that keeps deflationary spirals from accelerating.

Voldemort syndrome: Why the crisis can’t be named

These aren’t separate failures requiring separate technical fixes. They’re symptoms of a system-level contradiction that global institutions can’t acknowledge because doing so would require admitting what the postwar order actually was.

Technocratic elites invested entire careers in institutions premised on continuous growth, stable demographics, and the assumption that productivity gains would translate into shared prosperity through market mechanisms and occasional policy adjustment.

The World Bank finances development as if capital transfer creates purchasing power. The WTO manages trade expansion as if balanced current accounts reflect natural equilibrium rather than temporary demographic alignment. The IMF stabilises balance-of-payments as if currency crises are cyclical rather than structural symptoms of permanent demand dislocation.

None have frameworks for managing permanent demand contraction driven by demographic inversion across all major economies simultaneously.

Belt and Road was supposed to prove infrastructure investment could bridge the gap – or so the logic went. It demonstrated the opposite. Capital transfer without institutional capacity, without consumption-oriented investment, without demographic alignment between productivity gains and purchasing power, doesn’t create consumers. It creates debt.

So the crisis gets euphemised. “Slowdown” instead of collapse. “Adjustment” instead of breakdown. “Rebalancing” instead of the end of an appetite for consumption that sustained global capitalism for 75 years.

The language obscures because owning up to what’s ending requires acknowledging what it was: not a stable international order based on universal principles, but a historically contingent arrangement that worked because the hegemon had expanding demographics and could print the reserve currency to finance the consumption of everyone else’s production.

When that ends – and it is ending – nothing replaces it. Not Chinese state capitalism, which faces worse demographics. Not European social democracy, which is too small and too old. Not emerging market growth, which arrives without purchasing power.

What fragmentation looks like

The historical precedent exists. The 1930s triggered autarky, competitive devaluations, political breakdown. Bretton Woods, the EU, the WTO created transnational coordination only in the bloody aftermath – once the scale of catastrophe forced institutional innovation.

A sufficiently severe demand collapse might force similar innovation now: global redistribution mechanisms, cross-border fiscal transfers, demographic-adjusted trade frameworks designed to manage permanent imbalances.

But the current trajectory suggests fragmentation instead.

Tariffs proliferate as each country tries to hoard employment without building consumption. Immigration restrictions tighten, eliminating the one mechanism that could partially offset demographic decline.

Friend-shoring concentrates supply chains, reducing efficiency without creating demand.

Resource nationalism intensifies as commodity producers try to extract value from declining consumption bases.

The 2030s will be the hinge decade when China’s automation peaks, Western consumption based on retirement savings and property wealth depletes, and African demographics hit their contradictions simultaneously. The timeline mismatch will be undeniable. The policy tools will be exhausted. The institutional frameworks will be obsolete.

By the time crisis forces acknowledgement, it will be irreversible. The window for building alternatives will have closed.

Institutions exist to mediate contradictions before they become catastrophic. The question is whether they can adapt before demand itself disappears.

The evidence says not. Not because redistribution is technically impossible, but because the political mechanisms required operate at transnational scale whilst power remains national, because the timeline mismatch spans decades, and because acknowledging what’s ending requires acknowledging what the postwar order actually was – temporary demographic arbitrage, not permanent equilibrium.

If China with its governance capacity, strategic clarity, and $1 trillion couldn’t bridge the gap, nothing will.

But what does this abstraction – global “freefall” – actually mean for the people living through it?

7. The Human Stakes

For Chinese retirees

Born in the 1960s, it means pension systems that promised security but can’t pay out. The one-child policy that reduced their burden whilst in work now concentrates it whilst ageing.

Each working adult supports parents, possibly grandparents, and children who can’t find employment despite advanced degrees.

The property wealth they accumulated – often their only asset – has evaporated in deflationary spiral. A flat bought for ¥500,000 in 2010 is worth ¥300,000 now and still falling.

Healthcare costs surge whilst government revenues contract. They face old age in a society that automated away the consumption base before building adequate social insurance.

For American millennials

Born in the 1980s and 1990s, it means neither wages nor wealth. They entered adulthood during the financial crisis and accumulated student debt without corresponding wage growth.

Their parents bought houses for $150,000 that are now worth $500,000 – pricing their children out entirely. Their parents accumulated retirement portfolios that doubled and tripled whilst they were still in school.

Now automation and AI suppress their earning power whilst the stocks and houses they don’t own stop appreciating because nobody can afford to buy what productive assets produce.

The Boomer inheritance many expected will be spent down on end-of-life care rather than transferred. They’ll reach retirement without pension coverage, home equity, or financial holdings, in a country whose social safety net was always minimal and is now fiscally unsustainable.

For African youth

Born after 2010, it means reaching working age in economies where the industrialisation pathway has closed. Their grandparents were subsistence farmers. Their parents migrated to cities expecting manufacturing jobs that materialised in China and Vietnam but never reached Lagos or Nairobi.

By the time they reach adulthood, robots cost less than they do. The mobile phone in their pocket connects them to a global economy they can observe but not participate in. Education systems expanded but job creation didn’t.

The infrastructure China built facilitates resource extraction, not employment. The demographic dividend everyone predicted becomes a demographic burden when a billion young people have no productive role in an automated global economy and no purchasing power in an economy built on consumption they can’t afford.

What comes after demand?

These aren’t abstractions. They’re the human consequence of automation concentrating in ageing societies whilst consumption potential emerges in young societies without capital – and no mechanism existing to bridge the gap because the only institution that tried couldn’t overcome the structural contradictions.

The Marshall Plan worked because capital met young populations with institutional capacity during a period when all major economies’ workforces were expanding.

The 2040s will offer capital exhaustion, ageing producers, and young populations without institutions in a world where no major economy has an expanding workforce.

The mechanism that sustained growth for 75 years has inverted, nothing is replacing it, and the largest coordinated effort to build an alternative – China’s trillion-dollar BRI – has already demonstrated that the gap can’t be bridged through capital transfer alone.

What comes after demand isn’t adjustment or rebalancing or any of the euphemisms that policy elites deploy – it’s freefall.

Thanks for reading!

Best

Adrian

“Are these the shadows of the things that Will be, or are they shadows of the things that May be only?” Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol