Watch Iran’s Praetorians, Not Its Protesters

The regime won’t fall to protesters. It might fall to its own guards.

Grüezi!

1. What barks. What bites

The question everyone asks about authoritarian regimes is the wrong one. We keep asking when the protests will reach critical mass. The better question? When will the people with the guns turn them around?

Mass protests topple regimes not through their own force but by creating conditions for elite defection. The crowd in Tahrir Square didn’t defeat Mubarak’s military; the military decided Mubarak was expendable.

The Romanians who jeered Ceaușescu didn’t storm his palace; the army calculated that defending him would be costlier than abandoning him.

Ben Ali fled Tunisia not because protesters tore down his defences, but because his military refused to become his executioners.

Authoritarians face two particular problems. The first – controlling the masses – is the one the media barks over. The second – preventing defection by the elites who prop them up – is the one that actually bites them.

Of the 660+ authoritarian leaders who left office between 1946 and 2008, over 40 per cent lost power through coups, forced resignations, mass uprisings, or assassination. Armies, security services, or close confidants are responsible for most of these “exits.”

The Islamic Republic of Iran has understood this for nearly half a century.

So what looks like indiscriminate brutality is actually an instrument for preventing the coordination cascade that would bring the regime down.

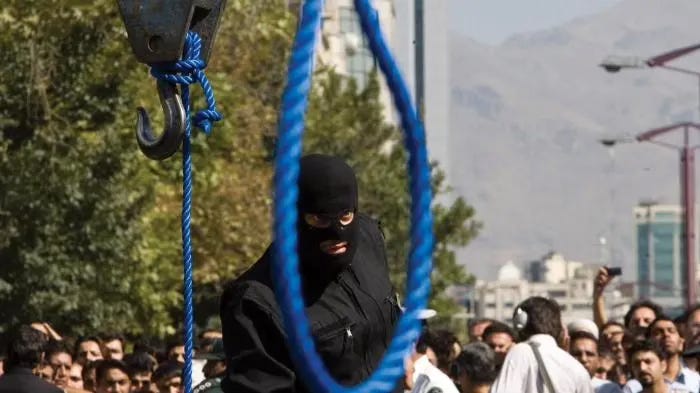

2. Who to hang?

Mass protest movements face a collective action problem. Taking part is individually costly – you might be arrested, tortured, or killed – but collectively beneficial.

Everyone would gain from regime change, but any individual protester bears disproportionate risk.

The regime’s calculus? Ensuring that the expected cost of participation exceeds the expected benefit – particularly for those whose defection would matter most. This requires calibration.

Too little violence, and movements grow (Syria in early 2011). Too much, and you trigger the very elite defection you’re trying to prevent (Romania 1989).

The optimal strategy operates on three levels.

First, selective brutality. The regime doesn’t attempt to repress everyone equally – that takes up too much resource and it can backfire by making grievances universal.

Instead, it targets movement leaders, visible early participants, and anyone within the security apparatus showing a little hesitation.

Take the 2022–23 ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ protests. Security forces killed over 500 demonstrators. In Zahedan alone, ‘Bloody Friday’ on 30 September 2022 saw 104 people killed in a single day.

But afterwards, arrests focused on activists, journalists, and lawyers – the organisers rather than the mass participants.

Second, public hangings. Executions serve a function beyond punishment. The regime took pains to publicise the hangings of young protesters like Mohsen Shekari and Majidreza Rahnavard – both executed within weeks of arrest in December 2022.

The signal? Participation in protests carries not just the abstract possibility of arrest and imprisonment, but rapid, public death.

When your neighbour’s son is executed, the question shifts from ‘will I join?’ to ‘will I risk my child?’ Iran Human Rights reported nearly 1,500 executions since the protests began, and the rate at which the death penalty was imposed is double that of the pre-protest period.

Third, making the guards complicit. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps isn’t just a security force – it’s an economic conglomerate controlling an estimated 35–50 per cent of the Iranian economy through front companies, foundations (bonyads), and construction conglomerates like Khatam al-Anbiya.

Senior commanders have vast personal stakes in the regime’s survival. The security apparatus has engaged in repression for so long that defection becomes personally dangerous. If you’ve participated in violence against protesters, your fate is tied to the regime’s.