The Leisure Trap

Why the lazy-European-hustling-American-hardworking-Chinese story is about to collapse

Grüezi!

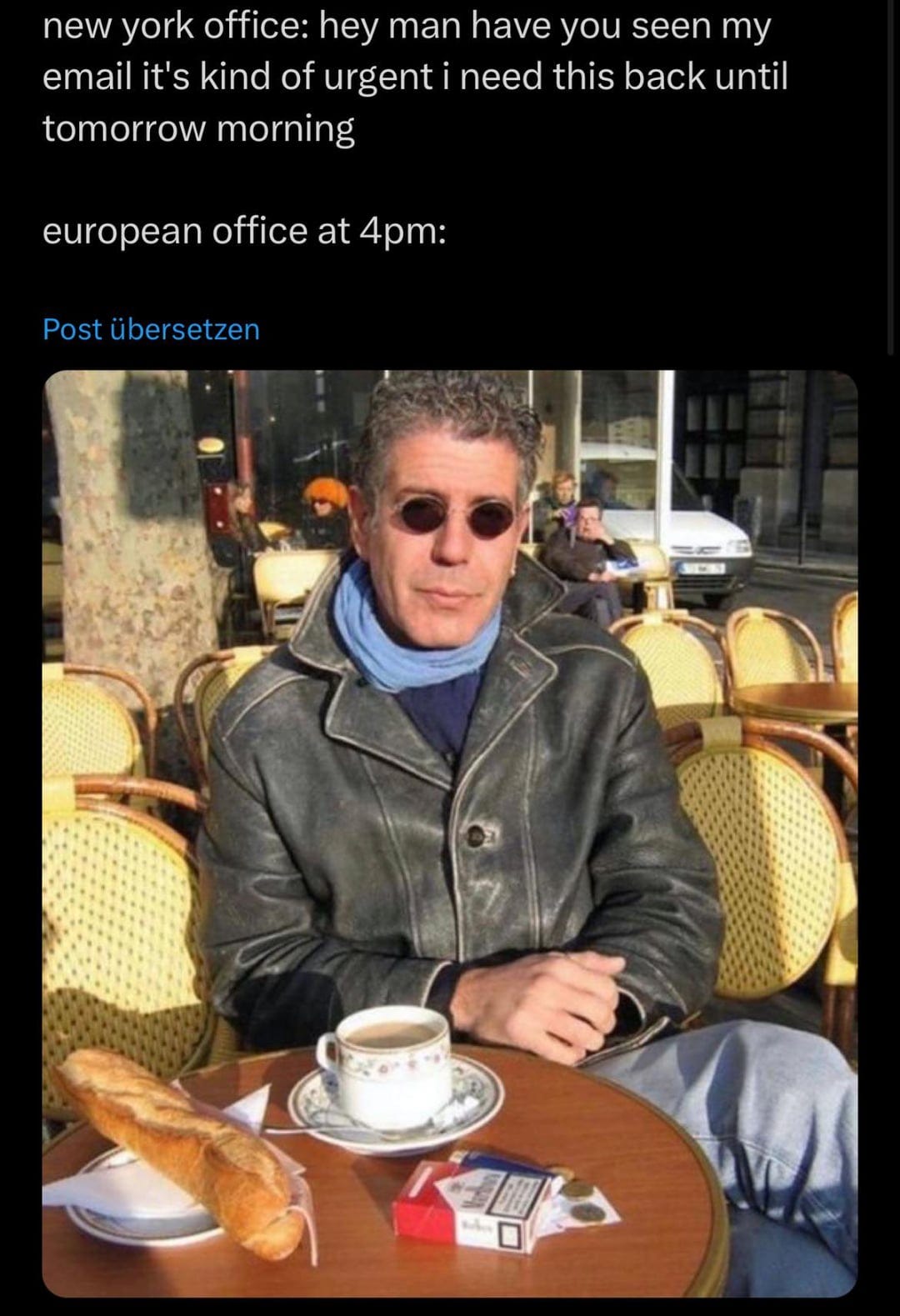

1. The Bourdain problem

The internet loves this picture of American chef Anthony Bourdain at a Paris café – shades, sandwich, coffee and cigarettes. Other captions?

Europeans watching DeepSeek overtake ChatGPT on Apple App Store;

Unemployed friend at 2pm on a Monday.

This meme is actually identifying a capability gap with trillion-dollar implications.

Lazy Europeans sipping wine from their sun-loungers in August whilst the continent gently deindustrialises. Americans bustling through 60-hour weeks and side hustles for the dream. Chinese workers relentlessly building the future at 996 pace – 9am to 9pm, six days a week.

Policy follows meekly behind national temperament.

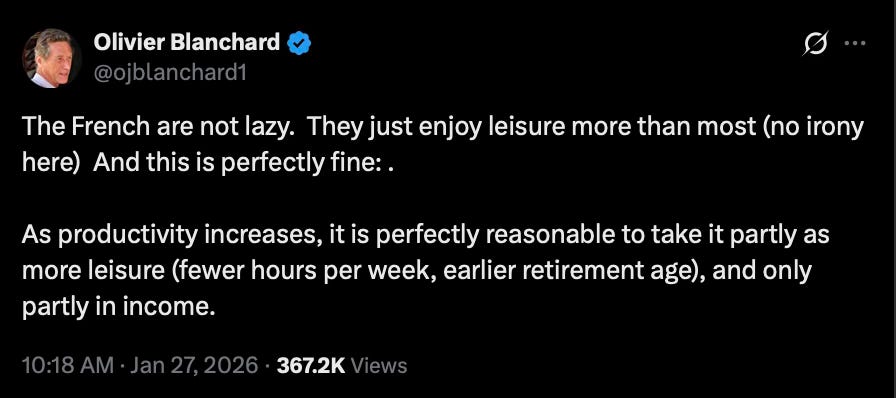

Except the data tells a different story. A debate broke out this week between two heavyweight economists – Olivier Blanchard and Jesús Fernández-Villaverde – and it suggests the stereotypes are wrong.

Blanchard, former chief economist of the IMF, posted a little online provocation: the French aren’t lazy, they just enjoy leisure more.

As productivity rises, it’s perfectly reasonable to take the gains partly as time off rather than income. Who’s to say the Americans have it right?

Fernández-Villaverde pushed back – not on the conclusion, but on Blanchard’s framing. His question is more interesting: where do preferences come from?

Preferences for work and leisure aren’t fixed national traits. They’re products of economic development itself.

The standard economic move treats these preferences as given. The French prefer leisure, the Americans prefer consumption, the Chinese prefer work. Economists shrug and move on.

But this assumes away the most interesting question. What if decades of policy, institutions, and development didn’t just constrain choices – what if they created preferences?

If so, the chilled European meme isn’t capturing a fixed cultural trait. It’s describing a developmental stage that other countries will reach. Including China.

2. Leisure’s a skill, skills need practice

Fernández-Villaverde borrows from Gary Becker and Kevin Murphy’s 1988 paper on rational addiction. Their insight: some things take practice to enjoy.

Fine wines require experience to savour. You can train as a sommelier, not as a chocolate-chip cookie connoisseur.

Extend this to leisure itself. Appreciating a three-hour lunch, discovering the charming streets of Lyon, sitting at a café doing nothing – these aren’t passive activities. They’re ‘skills’ that compound with practice.

The French have accumulated what Fernández-Villaverde calls ‘leisure capital’: generations of know-how in making free time genuinely enjoyable.

Americans, by contrast, have accumulated ‘work capital’ – skills at networking, career management, the side hustle. Plus they’ve ‘learned’ to enjoy and value things that require high incomes: the SUV, the basement home theatre, the lake house.

American returns to work are higher because Americans have invested in making work and its fruits rewarding.

Fernández-Villaverde’s observation rings true: self-made billionaires are often terrible at leisure. Their children are excellent at it.

The kids accumulated leisure capital when they were young; the parents never did.

3. Marxist historians FTW

The idea that economic structures reshape what people want isn’t new – it’s just been exiled from mainstream economics.

E.P. Thompson’s 1967 classic ‘Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism’ showed how the factory system didn’t just employ workers differently – it remade their relationship to time itself.

Pre-industrial work was task-based: you worked until the job was done. Factories required co-ordination. You clocked in and clocked out.

Within two generations of the Industrial Revolution, punctuality became important. Not because employers demanded it (they did), but because workers internalised it. The discipline moved from an external demand to an internal preference.

Thompson wrote about the imposition of work-discipline. Fernández-Villaverde asks whether the same mechanism runs in reverse.

If decades of shorter work weeks and longer holidays can reshape how people think about time – if the French have learned to value leisure the way the Victorians learned to value punctuality – then preferences aren’t fossilised. They’re flexible.

4. Tax doesn’t explain everything

Conservative economists, like Nobel prizewinner Edward Prescott, have long insisted that everyone’s preferences are the same and tax rates explain everything.

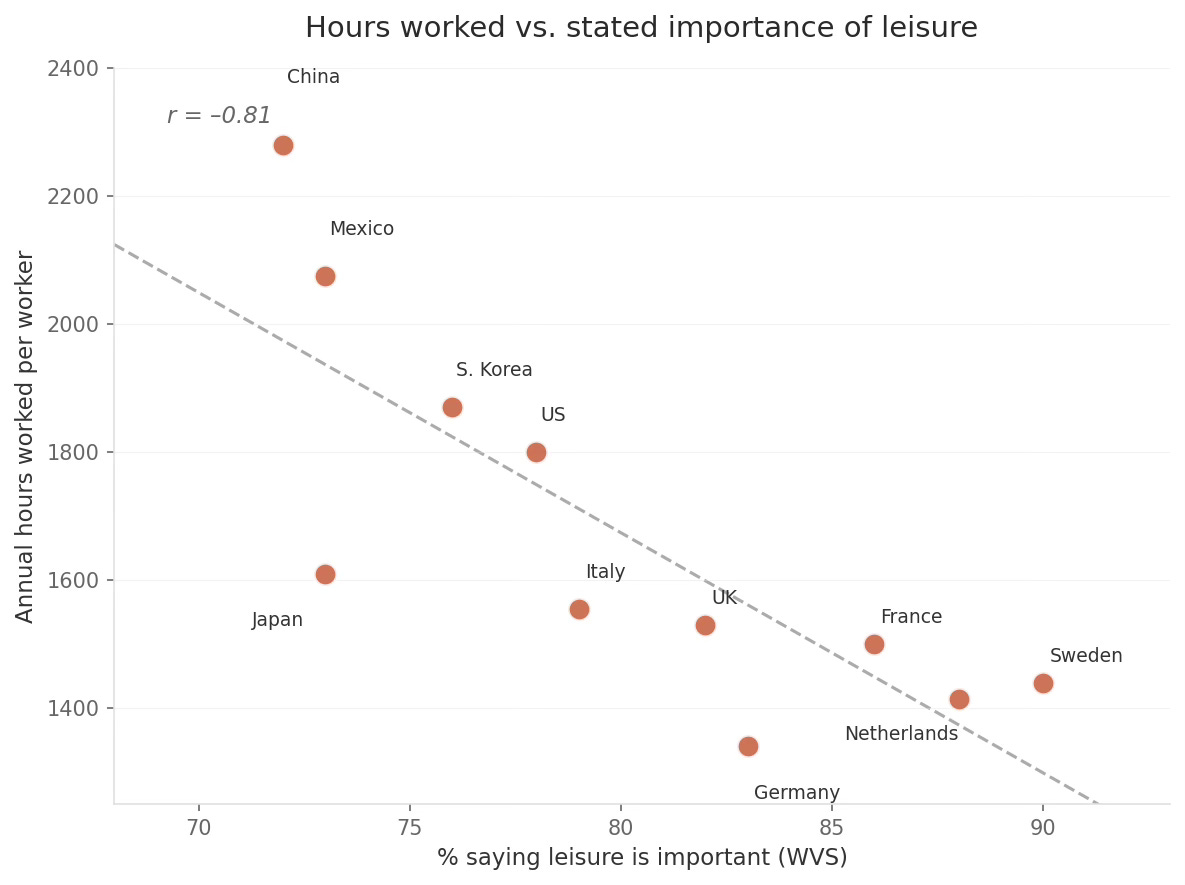

But surveys don’t show that.

Countries that work more hours also value work more. China, Mexico, and South Korea – the longest-hours countries – show the highest agreement that ‘work should always come first’.

Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden show the opposite.

If Prescott was right, German workers should be bristling with frustration at being prevented from working by high taxes.

They should want to work American hours but be deterred by the price.

Instead, they report genuinely preferring leisure.

People’s attitudes aren’t compensating for constraints. They’re aligned with behaviour.

5. Policies don’t shift preferences

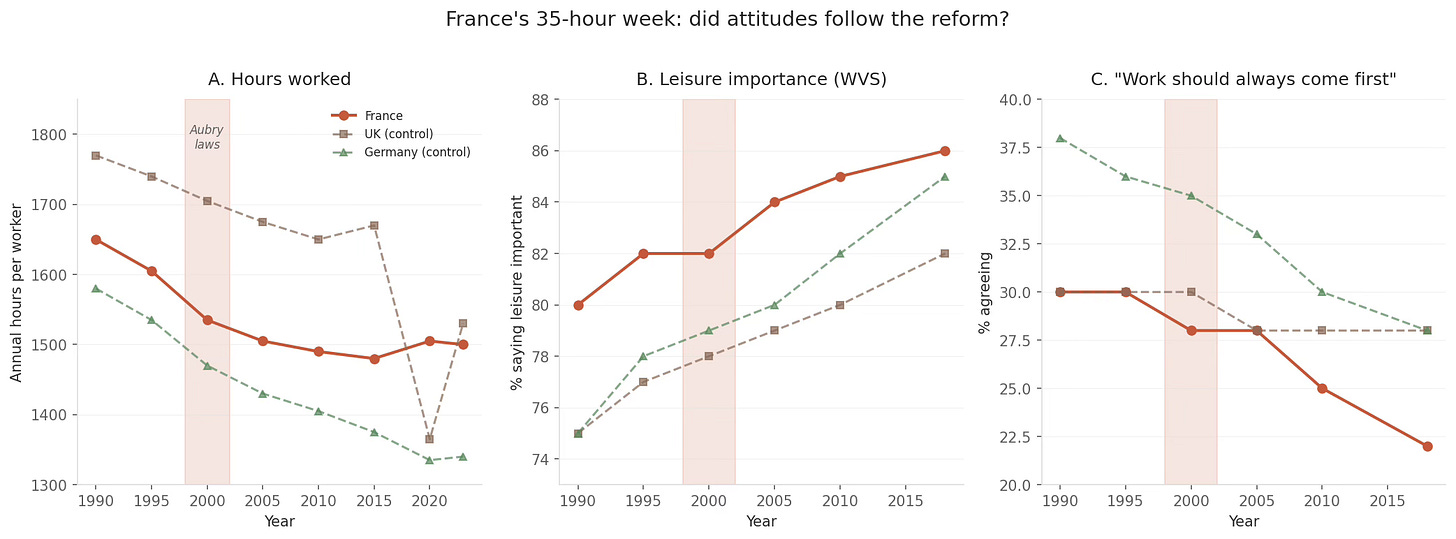

If policy shaped preferences, you’d expect France’s 35-hour week (brought in back in 2000) to have supercharged the French preference for taking time off.

The reform should show up as France pulling away from other countries in surveys.

But it doesn’t.

Between 1990 and 2020, the French shifted about 6 percentage points toward valuing leisure and 8 points away from ‘work should always come first.’ But so did the US (+6, –8). So did the UK (+6, –8). And Germany moved even further that way (+8, –10) – all without a 35-hour law.

All Western countries are drifting in the same direction, regardless of specific policy choices.

France may have the 35-hour week because of French politics. But it didn’t drive French preferences. In a very un-Gaullist way, they just followed along with everyone else’s.

Preferences are clearly being shaped by something – they’re changing everywhere, and they correlate with behaviour.

But that something may not be policy. It may be development itself.

6. East Asia is the natural experiment – and tang ping is the result

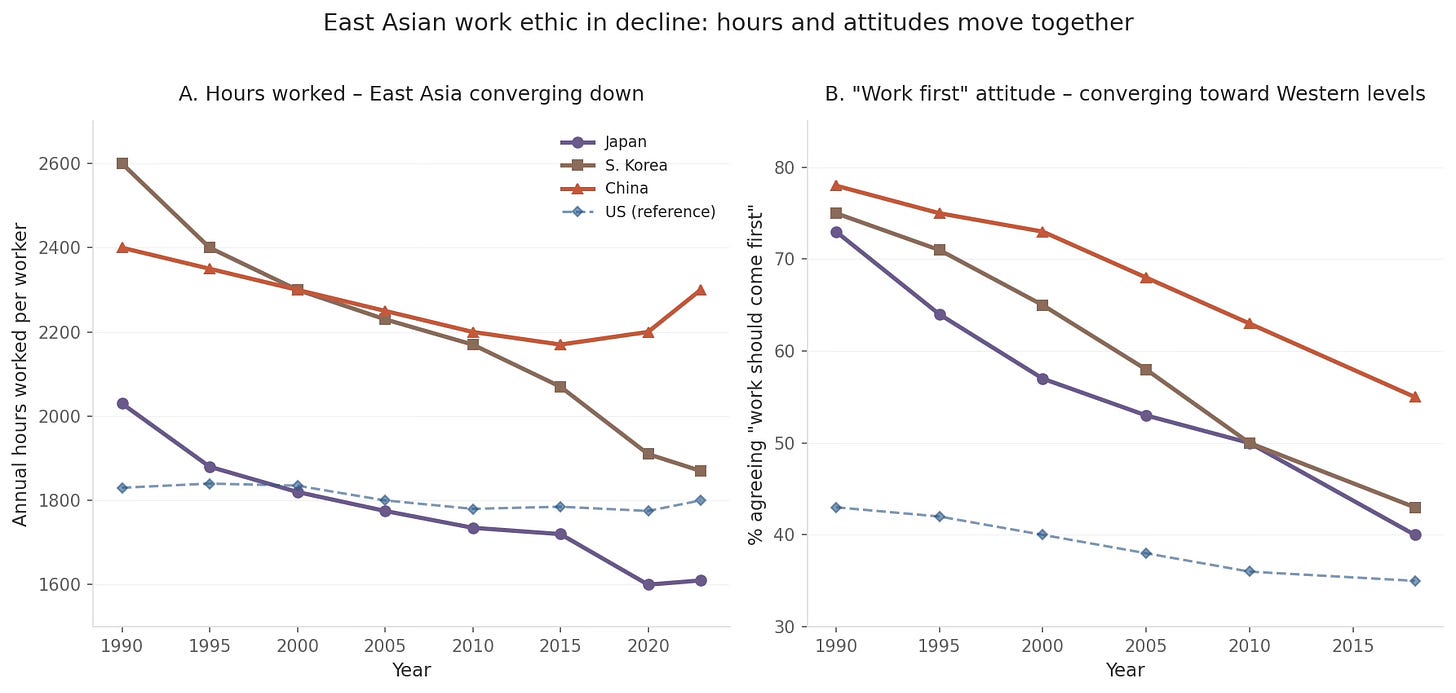

The most striking evidence comes from Japan, South Korea, and China. All three show steep, parallel declines in both hours worked and ‘work should come first’ attitudes over the past three decades.

They’re converging toward Western levels from very different starting points and with very different types of policy regimes.

Japan has strong labour protections. Korea has weak ones. China has active ideological promotion of work – Xi Jinping’s ‘New Era’ rhetoric explicitly links individual struggle to national rejuvenation.

Yet all three populations are moving in the same direction: away from putting work first, and towards valuing leisure.

China’s case is the sharpest. The tang ping (’lying flat’) movement emerged in 2021 as young workers rejected the 996 culture that had become normalised in the tech sector.

This wasn’t organised labour action. It was individual ‘slacking’ – preference revealed through non-participation. And it happened despite decades of pro-work propaganda.

Young Chinese who grew up with smartphones and disposable income are becoming more like their Japanese and Korean peers.

7. The geopolitical case against chill

Alex Imas, an economist at Chicago Booth, put it bluntly: ‘Leisure does not buy security and a trade surplus.’

This is the geopolitical case against chilling out. If the Chinese will work 996 and the French won’t, then joie de vivre is a strategic liability. Leisure is for countries that don’t face serious competition.

Blanchard pushed back: ‘You are saying that if a country decides to decrease hours worked, and has 10% less income, it is doomed?’

But both are assuming China’s work-maximisation is permanent. It isn’t.

You can’t build strategy on the assumption your competitor’s workforce will accept 996 indefinitely when their own children are already lying flat.

And American work-maximisation? US economist Brad Setser wryly suggested that France should take the US to the WTO for its ‘limited amount of paid vacation … a massive restriction on trade in services.’

The American work ethic is not ethical – it’s a trap. Americans can’t take leisure even if they wanted to.

Everyone still wants to build industrial policy on labour assumptions that development and demography are eroding.

The stereotypes aren’t types. They’re way stations. And right now they’re all headed to the same destination.

Thanks for reading!

Best,

Adrian

From Julia Child’s My Life In France: “When American experts began making “helpful” suggestions about how the French could “increase productivity and profits,” the average Frenchman would shrug, as if to say: “These notions of yours are all very fascinating, no doubt, but we have a nice little business here just as it is. Everybody makes a decent living. Nobody has ulcers. I have time to work on my monograph about Balzac, and my foreman enjoys his espaliered pear trees. I think, as a matter of fact, we do not wish to make these changes that you suggest.”

After reading Benjamin Hunnicutt (e.g., _Free Time: The Forgotten American Dream_), I concluded that the US might appreciate leisure as much as Europe does, if not for post-war macroeconomic choices.