I Was In The Room

Oxford, Starmer, and the Mail’s Farage defence.

Grüezi!

Forgive the walk down memory lane…

1. The Bait

On 7 December 2025, the Mail on Sunday splashed “KGB’s toxic propaganda machine” across a story about the young Keir Starmer.

The timing and the contrast were intentional. Their object was to defend Nigel Farage by slurring Starmer.

It was barely twenty-four hours after the Guardian had published testimony from over a dozen of Farage’s former classmates alleging that he made antisemitic remarks as a schoolboy, including telling a Jewish peer “Hitler was right” and “gas them” while hissing to simulate gas chambers.

A day later the Mail headline promised Cold War espionage. Soviet influence operations. A future Prime Minister compromised by Communist intelligence.

The story was a thin cuttings job, rehashing a trip to a Czech work camp they’d unearthed in June – when their own security expert called it “forgivable youthful naivety.”

To this, they added a student magazine that, by their own admission, “sold only a handful of copies” and which its founder conceded “no one read.” Some articles attacking Margaret Thatcher. And an appeal for a Portuguese brigadier signed by Tony Benn and Noam Chomsky.

And buried deep in the piece, a bitter ex-student and brief fellow traveller calling Starmer “an empty suit.”

The article declares its purpose quite plainly: “the Prime Minister’s decision to get involved in a row about what a rival politician allegedly did at school... inevitably invites scrutiny of his own youth.”

The Mail is not interested in Farage. It merely wants cover. How can you defend targeted antisemitic abuse of Jewish children? Teenage racism? The Mail knows that the best form of defence is attack.

Its framing treats Farage and Starmer’s younger years as equivalent. They are not equivalent. But now they sit side by side in the news cycle, and that’s enough.

I was in the Oxford University Labour Club with Keir Starmer. I also had to endure listening to the Mail’s “star witness” speak. Here’s what actually happened.

2. Norfolk

I joined the Labour Party in rural Norfolk in the early 80s as a teenager. It wasn’t what you’d picture.

My father was in and out of work. More out. I knew what unemployment did – not the statistics, the human cost. Watching your father shrink. The demoralisation, the pain, the humiliation of it.

My brother’s joinery apprenticeships kept collapsing as his employers went bust. One after another. Boatbuilding, food processing, light industry. All the jobs seemed to be disappearing.

Rural Norfolk was a desert for Labour. Tories would uproot our flimsy election posters. The local council was stuffed with worthies who spent nothing on education or any other service – they still thought the population belonged in the fields, even though there had been no jobs there for decades. Norfolk is still one of the least socially mobile counties in Britain, but that’s another story.

Labour meant something specific to me. The local party functioned as a dissident discussion group run by a couple of idealistic Irish academics. We talked about how to change things. How to get people back to work. How to rebuild what was collapsing around us.

Then I went to Oxford.

3. The Shock

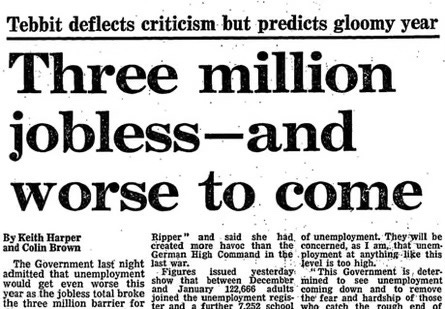

Oxford in the mid-80s: basking in the jeunesse dorée nostalgia of Brideshead Revisited on TV, whilst over three and a quarter million people were jobless. Over one in eight of the workforce – the highest since the Great Depression.

And the university’s Labour Club debated gay rights and feminism.

These weren’t unimportant. They mattered. And they still matter. But there’s something about watching some Oxford students – comfortable, credentialed, connected and destined for professional success – adopting the language of victimhood. It sat badly with me then and it still sits badly now.

The performative cost was zero. The unemployment figures were someone else’s problem. My concerns – the concerns I’d brought from home, from seeing the world fall down around me – felt sidelined. Irrelevant to the real business of the room.

Fellow Labour students quickly identified me as a reactionary. That meant something different back then. It meant caring about electability. About winning. About the people who needed a Labour government, not a seminar.

The purity police didn’t see it that way.

4. The Invisible Hand

Someone controlled who spoke. I never figured out who.

Student politics looks chaotic from outside. Passionate speeches, factional warfare, great causes. “Maggie Maggie Maggie! Out out out!”

Inside, the club ran on machinery. Someone decided which motions reached the floor. Someone managed who got called. Someone froze people out. Reality was rarely allowed to impinge on procedures.

I sat at the back a couple of times with another retrogressive, David Miliband. He’d occasionally speak up – a voice of reason when things got too ridiculous. Stephen Twigg spoke up more. Chair of the OUSU Lesbian and Gay Committee, elected onto the executive on the Labour Club slate.

I kept my head down. The loud ones – the true believers, the factional warriors – burned bright. Most of them burned out, or at least set aside their politics for professional pursuits.

Twigg went on to beat Portillo. Miliband headed a think tank before a career in the Cabinet.

One of the firebrands became Prime Minister.